Freud Had a Couch Not an Exercise Plan: Seriously? Mental Wellness Without Movement?

A long time ago, the United States had no laws against drunk driving. Operating a machine made of metal and glass at high speed while unable to think clearly seems obviously dangerous. But for a long time, no one paid much attention to what was self-evident.

This happens in other areas too: washing hands before medical exams, checking for bombs before boarding a plane.

Sometimes the world is slow to recognize the obvious and must learn through hard experience.

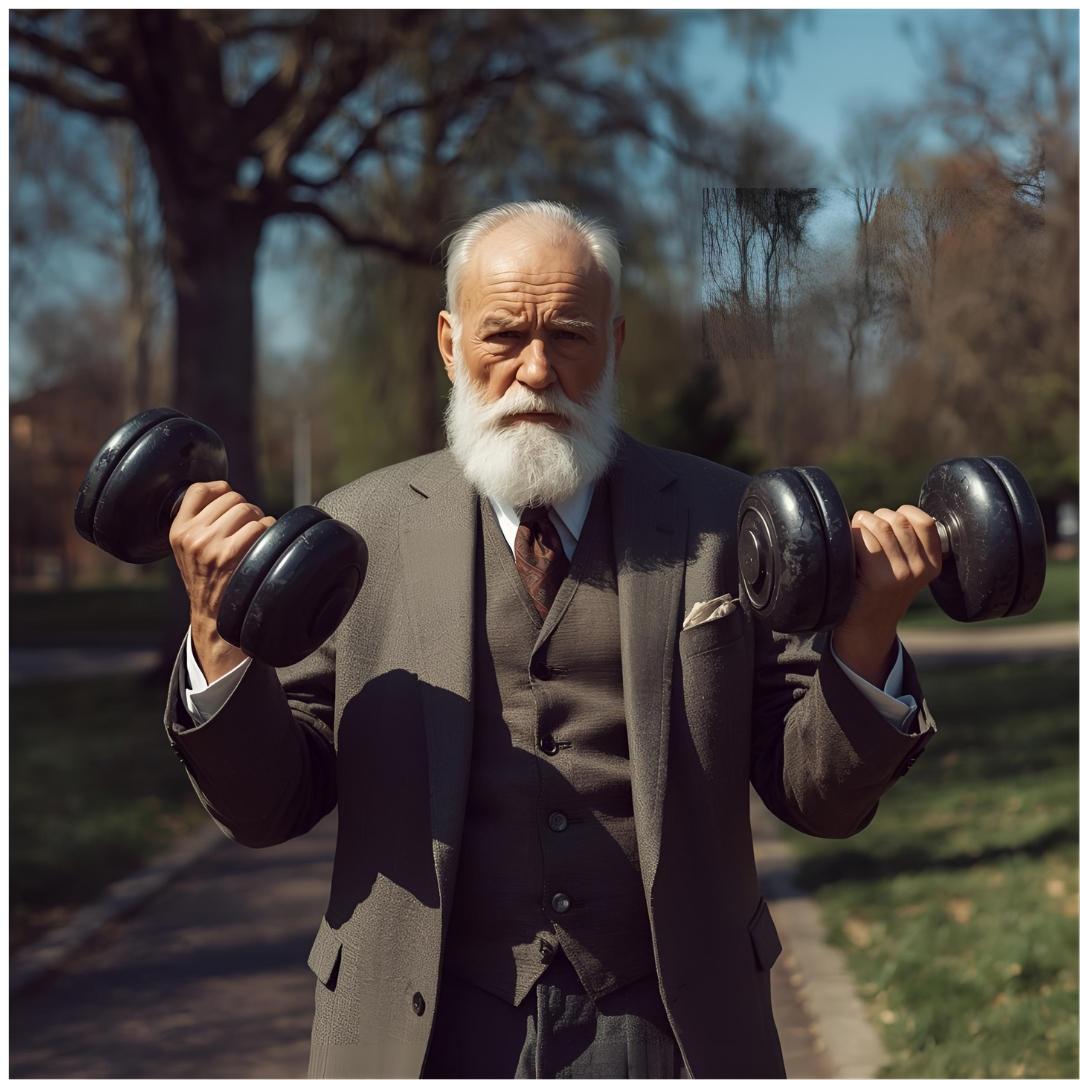

Many people may not know that Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) was a neurologist. That means he had training and understanding of how the brain and nervous system function. Freud later became a major influence on modern psychotherapy through his ideas about psychoanalysis and what came to be called “the talking cure.”

But here’s something many people haven’t considered deeply: Freud didn’t exercise.

While Freud did walk and hike occasionally, he had no knowledge of modern exercise science—a field shaped in part by the physical culture movement—and little personal experience with physical activity beyond casual strolls.

By contrast, William James (1842–1910), a formative influence on modern psychology, participated in a wide variety of physical pursuits: tennis, skating, bicycling, horseback riding, and mountain climbing.

Like early figures in the physical culture movement, James turned to exercise to address early struggles with illness. It’s no surprise that James’s psychological theories pay attention to the impact of physical sensation on the mind, while in Freud’s work, mental processes take center stage.

Meanwhile, during the same years Freud explored the mind, Eugen Sandow (1867–1925) was radically transforming the understanding of exercise.

Below are three simple examples of how the body directly shapes mood, energy, and cognition.

The fact that many foundational figures in psychology, like Freud, lacked direct experience of the concrete impact of the body on the mind represents a clear gap in their work. They theorized about thought and emotion while overlooking the moment-to-moment biochemistry of the body that constantly shapes how we feel and think.

Just as we inherited a world where drunk driving was not taken seriously, today we inherit a health system where exercise is largely excluded from domains where it should likely be a first-priority consideration: mental and physical health.

When the Body Drives Mood

Low blood sugar, or hypoglycemia, is a medical event in which glucose falls below the level required for normal brain function. The nervous system reacts immediately: the body releases stress hormones such as adrenaline and cortisol, triggering a cascade of physiological responses. The heart races, muscles tense, and energy is prioritized for survival.

These changes produce predictable shifts in emotion and cognition: irritability, anxiety, confusion, difficulty concentrating, and sometimes panic or aggression. Importantly, these emotional states are caused by the body, not conscious thought. The mind responds to signals from the body, not generates them independently.

Emotions Caused by Food Manipulation

For anyone who has intentionally manipulated diet to impact body composition - lowering body fat, building muscle, or both - the effects on mood and energy are self-evident.

At low levels of body fat, irritability, fatigue, low motivation, and emotional fluctuations aren’t just side effects; they are part of the process.

Every meal, caloric adjustment, and macro tweak has the potential to create measurable shifts in how a person feels, thinks, and reacts.

To an experienced fitness practitioner or physique athlete (i.e. bodybuilder), it’s like saying someone standing outside will get wet - it’s obvious, but only if you’ve ever stood outside in the rain.

Even today, with high levels of obesity and metabolic disease, few people have experienced this kind of systematic manipulation of food and its effects on emotion. People may intellectually understand that food and exercise influence mood, but they haven’t navigated it over long periods with professional guidance.

This kind of insight was completely absent from Freud’s work. His theories were developed by a sedentary man who never saw firsthand how food and exercise shape mind and emotion in dynamic, measurable ways.

There’s a reason fitness professionals don’t feed athletes randomly. Strategies like carb cycling allow them to manipulate energy and mood by controlling what fuel the body receives—and when. This is not about coaching psychological states; it’s about understanding where the athlete is physiologically, given their training load, fatigue, and output. The athlete’s feelings are one readout of the body’s state.

Emotions Caused by Exercise

Exercise provides some of the clearest evidence that the body drives emotional and cognitive states

Aerobic activity, like circuits, running, and cycling, can produce the “runner’s high” - a surge of endorphins and endocannabinoids that reduces anxiety and creates a feeling of mental well being, even though the precise mechanisms remain partially unknown.

Resistance training (i.e. weight lifting) and other structured movement can also reduce anxiety, change energy levels and improve overall mood.

Exercise also changes pain perception: what once felt uncomfortable becomes more manageable as the nervous system adapts.

These changes are not the result of conscious thought or psychological reframing. They are physiological responses. The brain reacts to chemical, hormonal, and neural signals generated by the body, illustrating that movement itself is a potent modulator of how we feel, think, and experience the world. All of this would have been outside Freud’s personal experience and professional consideration.

Meta-analyses show that regular exercise not only eases symptoms of depression and anxiety but can also reduce the risk of developing them, sometimes performing as well as - or even better than - medication or cognitive-behavioral therapy for mild to moderate cases. But a sentence like that barely begins to deliver the experience of seeing hundreds of examples of the way exercise can make immediate, sometimes lasting shifts in how people feel and perform.

Recognizing the Obvious

The neurologist V.S. Ramachandran once made the point that if someone showed you a talking pig, you had two choices:

One response might be: “That’s not statistically significant.”

The other: “Holy cow. A talking pig.”

Sometimes it takes society a while to notice what is obvious.

Driving drunk is dangerous.

Exercise and food impact emotions.

When practitioners have exposure to physical movement, like William James, it shapes their professional outlook.

After all, how can you truly consider something you’ve never experienced in detail, had little professional training in, nor stopped to investigate? You can’t.

The origins of psychotherapy were limited by the narrow lived experience and scientific frame of its founders, and this has had lasting consequences for how mental health is conceptualized and treated.

Even today, in modern psychotherapy - we have examples of where the personal experiences of professionals such as Marsha Linehan informed the development of theories and practices (Dialectical Behavior Therapy).

Freud’s personal lifestyle and worldview clearly shaped his. Since he lacked deep experience with exercise and didn’t study the body as someone trained in exercise science or physiology would, his understanding of mental processes remained largely disembodied.

One lesson from the art and science of exercise is that human bodies, despite shared similarities, are incredibly unique in how they move and what they can do. Working with them requires both a high degree of art and a firm grounding in scientific principles.

So while there is much we can learn and benefit from in the world of psychology inherited from innovators like Freud, it’s time for society to begin to update what we know about how the body impacts the way we feel.

Had Freud Experienced Exercise

Had Freud had deeper background and experience in exercise and other forms of science, he might have asked questions such as:

If mental distress can be both created and alleviated by manipulating food and activity, what does that tell us about how the human mind works?

How does nutrient availability impact the function of cells and the related energy levels of an individual?

What don’t we know about endorphins and the endocannabinoid system that might be involved in the feeling states people experience when they exercise?

Why do we not fully understand what makes people tired? And how could understanding that inform our understanding of fatigue outside of exercise?